The Simple Yet Effective Cornell Method Helps You Take Better Notes

A science-backed structure for deeper learning and stronger memory — even on hectic days

Have you ever left a meeting or lecture and felt like the information evaporated? Or opened your notebook later and thought, “Wait… what was actually important here?”

You’re not alone. Most notes become information graveyards — full of words, but empty of meaning.

Back in uni, I’d scribble down everything — arrows, quotes, half-baked ideas. I felt productive. But later, flipping through those pages felt like reading someone else’s dream journal. Disjointed. Confusing. Useless.

The secret isn’t taking more notes.

It’s taking smarter ones.

Note-taking is more than a productivity habit. Done right, it’s a form of active learning that helps you:

Focus your attention,

Make sense of new ideas,

And recall them when you need them most.

I’ve explored complex systems like Zettelkasten and tools like RoamResearch. They’re powerful — but not exactly plug-and-play.

Sometimes, you just want a simple method that works — today.

That’s where the Cornell Note-Taking System comes in.

In this newsletter, you’ll get a simple and science-backed method to take better notes — even on hectic days. You can use this system for lectures, online courses, and meetings. Ultimately, this method can help you become more efficient while studying, working, and learning.

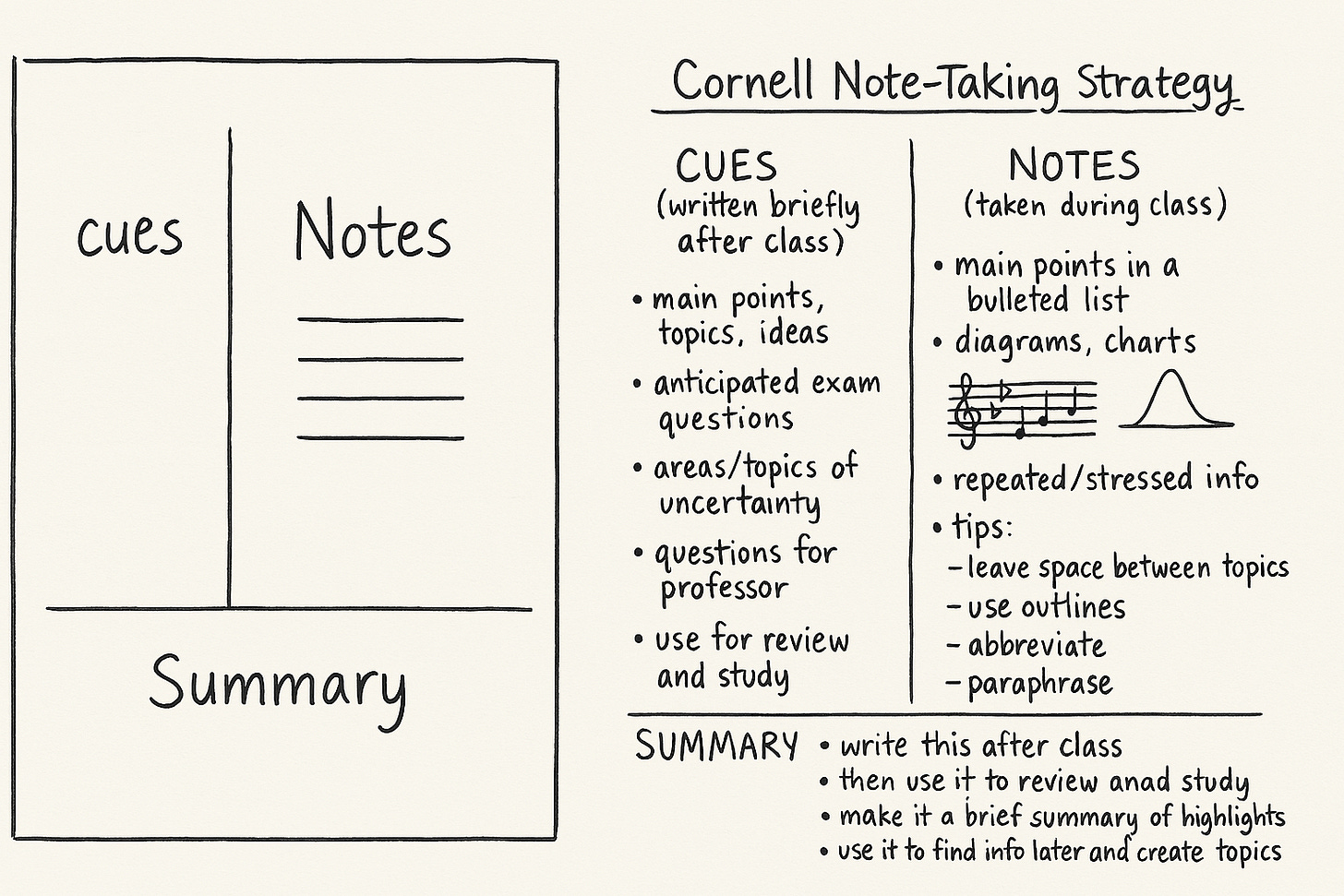

What Is the Cornell Method?

Developed by Walter Pauk at Cornell University, this method turns a blank page into a memory machine.

It helps you engage deeply with new information — not just once, but multiple times — by structuring your notes into three parts:

Main Notes (Right side, largest section):

Write down key ideas as you go — whether you’re in a meeting, lecture, or watching a course. Focus on capturing meaning, not every word.Cue Column (Left side):

Leave this blank while taking notes. Within a few hours, go back and add keywords, questions, or prompts that trigger recall. This is where real learning starts.Summary (Bottom of the page):

Within 24 hours, write 2–3 sentences that distill the main takeaways. What really matters from this page? What do you want to remember?

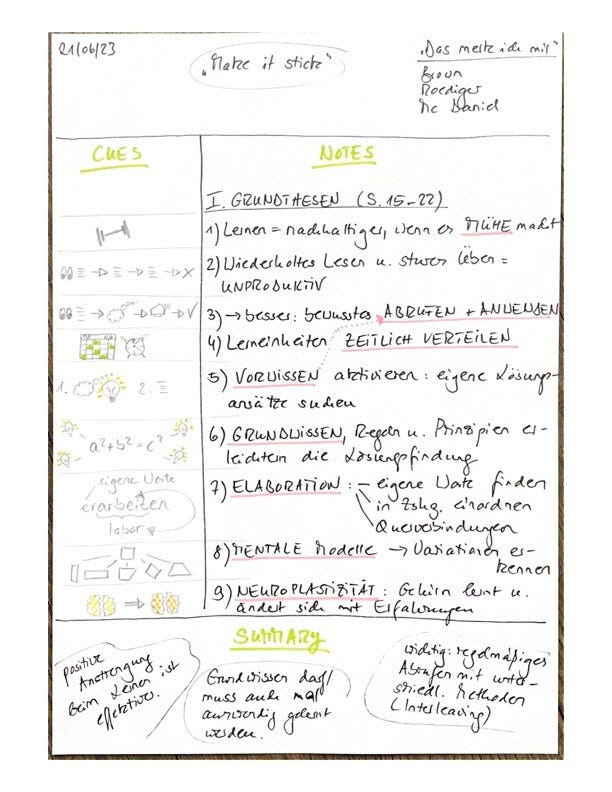

Here’s what this looks like in practice for a recent conference I attended in Singapore. See a section for cues on the left, notes on the right, and a summary of critical points on the bottom.

Eva Hörtrich used the Cornell Note-Taking Strategy to summarize “Make it Stick,” one of my favorite books on the science of learning.

How to Actually Use It (A Clear Workflow)

Here’s how to make the Cornell Method work:

During the session:

Write notes in the main section. Use bullet points, abbreviations, and simple visuals if they help. Focus on meaning, not every word.After the session (within a few hours):

Reread your notes and write cue questions or keywords in the left column. Try to cover up your notes and answer aloud — this strengthens recall.Later that day or the next:

Write your summary. What was this all about? What’s worth remembering in a week?When reviewing:

Cover the main notes, look at the cues, and try to answer. This is retrieval practice — and it’s one of the most powerful learning techniques known to science.

3 Cognitive Science Principles That Make It Work

1. Retrieval Practice

Every time you use the cue column to quiz yourself, you’re strengthening memory. The “testing effect” shows that trying to remember is far more effective than simply rereading.

2. Elaboration

Writing your own cues and summary forces you to rephrase and connect ideas. This elaborative processing is critical for deep understanding and long-term retention.

3. Organization

Cornell’s layout builds structure into your thinking. It helps you distinguish main ideas from details and spot patterns — the foundation of chunking and schema-building, key ingredients of expertise.

When taking notes with the Cornell method, there are two things you want to keep in mind.

Common Pitfalls (and How to Avoid Them)

🟡 Myth: More notes = more learning

Not quite. Writing more isn’t the goal — thinking more is. Don’t try to capture everything. Focus on capturing ideas worth remembering.

🟡 Skipping the cues or summary

It’s tempting to only fill out the main notes. But that’s like planting a seed and never watering it. The real magic of the Cornell Method happens after class — when you reflect, connect, and review.

🟡 Waiting too long to review

Spacing matters. Don’t delay. Use the method in full — and you’ll retain more with less study time later (or even better, set up a spaced repetition system).

Try This Today

For your next meeting, lecture, or podcast:

Divide a page into three sections (main notes, cue column, summary).

Jot notes during the session.

Add questions or keywords within a few hours.

Write your summary by the end of the day.

Resources and Further Reading

Cornell University Learning Strategies Center. (n.d.). The Cornell note taking system. Cornell University. https://lsc.cornell.edu/how-to-study/taking-notes/cornell-note-taking-system/

Keiffenheim, E. (2021, April 2). Zettelkasten’s 3 note-taking levels help you harvest your thoughts. Better Humans. https://medium.com/better-humans/zettelkastens-3-note-taking-levels-help-you-harvest-your-thoughts-58326840f969

Keiffenheim, E. (2021, May 25). The complete guide for building a Zettelkasten with RoamResearch. Better Humans. https://medium.com/better-humans/the-complete-guide-for-building-a-zettelkasten-with-roamresearch-8b9b76598df0

Rahmani, M., & Sadeghi, K. (2011). Effects of Note-Taking Training on Reading Comprehension and Recall. The Reading Matrix : an International Online Journal, 11, 116-128. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Effects-of-Note-Taking-Training-on-Reading-and-Rahmani-Sadeghi/85a8f016516e61de663ac9413d9bec58fa07bccd

Rawson, K. A., & Dunlosky, J. (2011). Optimizing schedules of retrieval practice for durable and efficient learning: how much is enough?. Journal of experimental psychology. General, 140(3), 283–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023956

Roediger, H. L., & Butler, A. C. (2011). The critical role of retrieval practice in long-term retention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15(1), 20–27.

Nye, P.A., Crooks, T.J., Powley, M. et al. Student note-taking related to university examination performance. High Educ 13, 85–97 (1984). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00136532

Wammes, J. D., Meade, M. E., & Fernandes, M. A. (2016). The drawing effect: Evidence for reliable and robust memory benefits in free recall. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 69(9), 1752-1776. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2015.1094494

Great method, thanks. I tried Roam Research for a while but it was expensive and I went back to using One Note.

Thank you! simple to use. Valuable!