Everything You ‘Know’ Has an Invisible Expiration Date

The same expertise that once was true might be slowly decaying. Here’s how to deal with it.

Welcome to issue #212 of the Lifelong Learning Club. I’m Eva, and each Wednesday I send you a free article to help you learn smarter and turn “one day...” into Day One. For the full suite of science-backed strategies, expert AI prompts, direct support, and a global community designed for consistent action, consider becoming a paid member.

Think about the most important thing you “knew” for certain five years ago.

Maybe it was a rock-solid business strategy, a core belief about your industry, or a non-negotiable truth about how the world works. Now, ask yourself honestly: Is it still 100% true?

If you’re anything like me, the answer is a little uncomfortable. Many of my own deeply held beliefs from just a few years ago now feel incomplete, if not outright naive, or plainly wrong.

I used to try to convince people close to me that eating a lot of a protein-focused diet is harmful. I used to believe the moon was unrelated to my cycle. I used to believe that making the world a better place works only through me giving it all (and burning out). I used to be convinced that homeopathy equals evidence-based medicine.

Some mental models are harmful to yourself. And then there are strongly held beliefs that are harmful to entire societies.

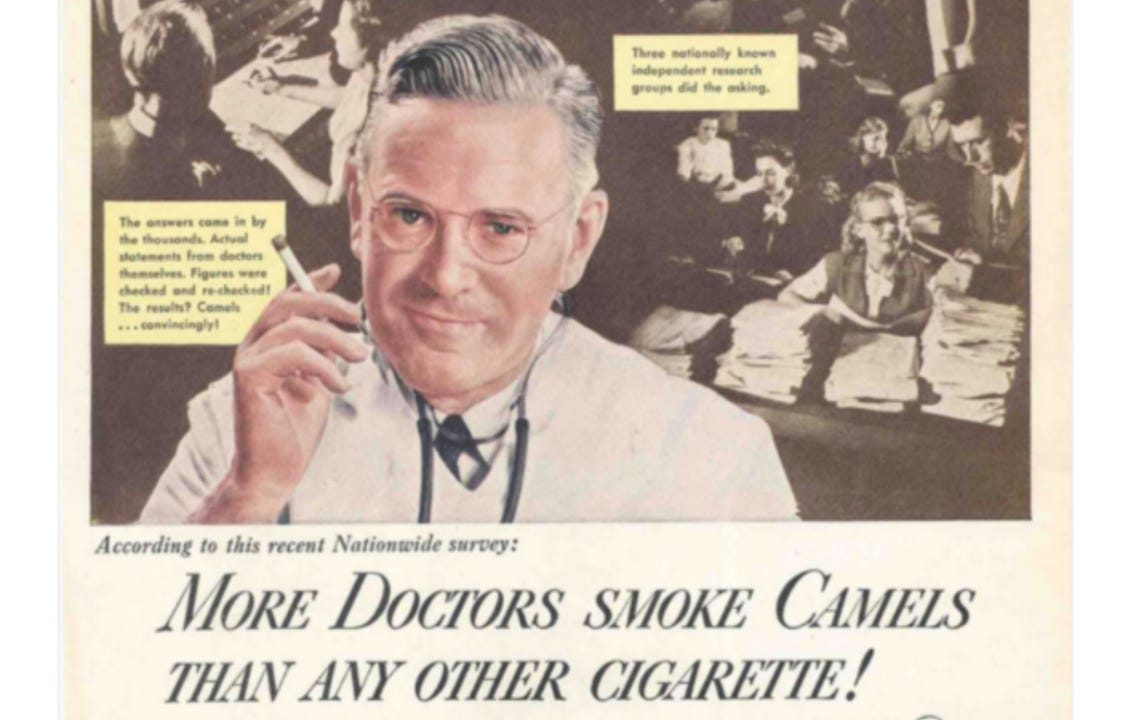

In the 1930s, doctors didn’t just fail to warn against smoking; they actively recommended certain brands for a smoother throat. These weren’t charlatans or fools. They were the most educated experts of their day, operating on the best knowledge available—knowledge that simply hadn’t expired yet.

This phenomenon is known as the “Half-Life of Knowledge”: the time it takes for half the facts in a particular field to be proven wrong or become obsolete. For medicine, that half-life is now as short as 18 months. Half of what a medical student learns in their first year will be outdated by their third.

The problem is, our own beliefs don’t come with a label on the bottom. We can’t see the invisible expiration date on our most cherished ideas.

This is the intellectual blind spot of our time: knowledge isn’t permanent. Most of what we consider truth today might not be “the truth,” or it may decay within a decade from now.

But what if you could learn to spot this decay before it expires? There’s a way to turn this uncomfortable truth into your greatest advantage—a system for evolving your beliefs and becoming a true lifelong learner.

A Mind Full of Expired Facts Is a Toolbox Full of Rusted Tools

It’s not ignorance that poses the greatest threat to our success. It’s the knowledge we’re most proud of.

The enemy is a silent, relentless process called Knowledge Decay—the invisible rust that accumulates on our expertise. It’s the reason why a brilliant strategy from 2020 feels clumsy in 2025, and why a core “truth” about your industry can quietly become a myth.

A mind full of expired facts is like a toolbox filled with rusted tools. From a distance, it looks impressive—packed with experience and credentials. But the moment you need to solve a novel problem or build something new, you find your most trusted instruments are brittle and useless. They break the moment you apply pressure.

This is why philosopher Bertrand Russell wrote, nearly a century ago, that “the fundamental cause of the trouble is that in the modern world the stupid are cocksure while the intelligent are full of doubt.”

Lifelong learners and curious minds understand that certainty isn’t a strength; it’s a liability. They know the purpose of learning isn’t just to affirm their beliefs, but to relentlessly evolve them.1

So how do we build an intellectual immune system that actively seeks out and replaces decaying beliefs before they make us obsolete? And how do we spot errors in our own mental models that are not serving, maybe even harming us?2

How to See the Expiration Dates on Your Own Beliefs

The idea here is to cultivate a few simple mental habits that act as an ongoing immune system against static and stubborn thinking. Take what feels helpful and ignore the rest.

1. Have Coffee with a Heretic (Metaphorically).

Your intellectual immune system gets stronger when it’s exposed to intelligent dissent. Don’t just wait for it to happen; actively seek it out.

Identify one of your core beliefs and go find its smartest critic. “Have coffee with them” by reading their book, listening to their most-cited podcast interview, or watching their most popular talk.

The most common intellectual error of our time is mistaking a lack of understanding for a moral victory. We caricature political opponents not because it’s always right, but because it’s easy.

The mission here is not to debate or win. The mission is to understand their argument so well that you can explain it for them. You are trying to find the strongest possible version of the opposing view.

This does one of two things: it either reveals a genuine weakness in your own position that you need to fix, or it forces you to sharpen your own logic, transforming a casual belief into a clearer conviction.

2. The One-Sentence Stress Test.

Most of our big beliefs are fuzzy. To stress-test a belief, make it solid. The next time you face a major decision, pause and ask yourself:

“What is the single sentence of belief that’s driving this entire action?”

Force yourself to distill it. For example, a startup founder might realize their belief is, “The only thing that matters right now is user growth at all costs.” A writer might find their belief is, “To be successful, I must publish on social media every single day.”

Once the belief is a single, clear sentence, it becomes fragile. You can hold it up to the light. You can ask, “Is that still true? Is it completely true?” This simple act of clarification is often enough to reveal the hairline cracks in what felt like solid ground.

3. Hunt for a Better Mental Model.

Changing your mind feels like a defeat. But upgrading the mental models you hold can feel like a victory.

When you feel stuck or when a belief starts to feel shaky, don’t ask, “Am I wrong?” Ask, “Is there a better mental model for this?” A mental model is simply a way of explaining how something works.

Take disagreement. One mental model views it as a threat to harmony that should be avoided. A more rigorous model sees it as the necessary friction through which true solidarity is created—a difficult, honest process required to build trust that can withstand pressure.

Another example of a mental model I used to hold is seeing love as a passive feeling you fall into. Seeing it as an active practice—a “love ethic” of care, commitment, knowledge, and responsibility—is another. Neither model is universally “right,” but one offers a radically different way to build a relationship, a community, and a life.

So the lesson here is that when you update your beliefs for a new mental model, you’re not admitting personal failure. It’s no identity threat. You’re simply looking for a more truthful tool. It transforms the painful process of being wrong into the exciting process of finding a better way to be right.

How to Treat Your Mind

In the end, you face a choice in how you treat your own mind.

The doctors who prescribed cigarettes weren’t malicious; their expertise had simply passed its expiration date without them noticing. They were the smartest people in the room, right up until the moment they weren’t.

It’s a reality we all face. The same expertise that builds your reputation today becomes the intellectual baggage that holds you back tomorrow.

Every time you encounter a new idea that contradicts what you believe, you stand at a crossroads. You can make the easy choice: to defend your territory, to win the argument, to protect the value of what you already know. This feels productive. It feels smart. But it is the slow road to stop learning.

Or you can make the harder choice. You can ask, “What if they’re right?” You can do the work to find the strongest possible version of the opposing view, not to concede, but to understand. You can choose to be a learner first and an expert second.

The choice isn’t between being right or wrong. It’s between building a bridge and building a wall.

Don’t defend what you know. Discover what you don’t.

I love this recent example by

, who writes, “I often cluster my reading and read 5-10 books on the same topic to ensure I get a well-rounded perspective. When I read only one book, the topic seems easy to understand. The same is true if I read several books where the authors’ perspectives are closely correlated (sharing similar values, working in the same intellectual field, and so on). I get a false sense of clarity. But if I read multiple uncorrelated books about the same topic, I get a real sense of confusion. The authors contradict each other! They use different frameworks, so I don’t know if they are talking about the same thing! What is this!? The confusion hurts my head and forces me to wrestle with the material. I have to do such things as reconstruct the arguments and evaluate them. I have to translate between the different frameworks to understand if they are talking about the same things. In this process, I win my own understanding.”It’s important to note here that many of our mental models are not errors of logic but survival strategies shaped by trauma. They once protected us, but later can limit us. Updating them requires not just reason, but compassionate inquiry into their origins.

"The same expertise that once was true might be slowly decaying. Here’s how to deal with it” - usually such things happen in three cases: change of execution context, change in the scale, and chane in the pace. New technology is usually devaluate previous experience due to differences in concepts and principles.

Thanks for a great article! I love the 3 very practical tips you provided on how to test and re-evaluate our mental models ! Now I just need to find a good mental model to keep these front and centre and put them into regular practise! :)