Why You Forget What You Read (And How to Fix It)

A practical guide to using evidence-based learning strategies to read, retain, and apply insights from any nonfiction book.

Think you’re learning when you're reading? Think again.

Most people believe reading equals learning. But if I asked you to explain key takeaways from the last five books you read, would you be able to?

I wasn’t.

A Bachelor's and Master's degree—both passed with honors—taught me how to learn for exams. But they didn’t teach me how to learn for life.

Leaving university, I felt like I knew… nothing. So, I did what any self-proclaimed knowledge addict would do: I read. A lot.

Fifty-two books a year.

But 80 books into my reading journey, something felt off.

Whenever a conversation revolved around a biiig, time-consuming book like Sapiens or Thinking, Fast and Slow, I struggled to recall anything beyond the broadest themes. No details, no key arguments—just vague familiarity.

Was I just bad at remembering?

Not at all. It wasn’t until I discovered the forgetting curve that I realized forgetting isn’t a personal flaw—it’s a biological feature.

Your Brain Is Wired to Forget

Unless you have a photographic memory, the idea that reading equals learning is miles away from reality.

Your brain is built to filter out most of what you consume. If it didn’t, you’d be drowning in irrelevant details, unable to focus on what truly matters.

This graph shows how quickly you forget new information over time unless you actively reinforce it. The curve drops sharply in the first few days, meaning most knowledge fades fast unless retrieved regularly.

Yet, most people act as if their brains are hard drives that automatically store everything they read. They race through books without engaging with them, mistaking reading for remembering (hello younger me <3).

If you actually want to retain and apply what you read, you need a different approach.

Here’s a 3-step system, grounded in cognitive science, that transforms passive reading into active learning—so you can recall and apply knowledge when it matters.

Step 1: Elaborate — "Explain-It-Yourself"

The Problem: Reading passively doesn’t strengthen memory. You need to engage with new knowledge.

The Science: When you elaborate on an idea—by explaining it in your own words and connecting it to what you already know—you deepen memory traces in the brain. Researchers Roediger & McDaniel call this "elaborative rehearsal", a proven way to encode information into long-term memory.

🛠 Try this now: Next time you read a book, pause after a key section and ask yourself:

How would I explain this to a 10-year-old?

Where does this idea connect with something I already know?

How could I apply this insight in my own life?

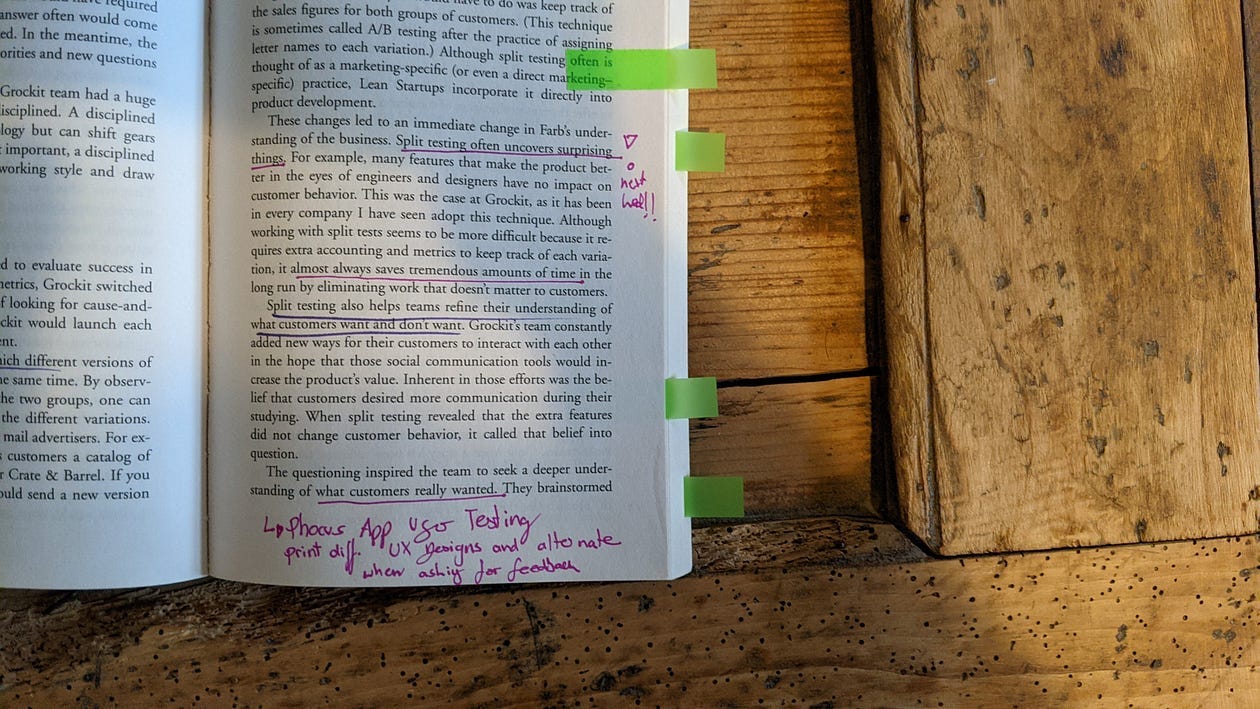

💡 Example: If you’re reading The Lean Startup, don’t just nod along to the concept of “validated learning.” Instead, explain it to yourself in simple terms, like:

"Instead of guessing what customers want, you test ideas with real users as fast as possible—so you don’t waste months building the wrong thing." This forces your brain to process the information deeply, creating more memory retrieval cues.

Step 2: Retrieval — “Write without Looking”

The Problem: Simply reviewing notes or re-reading a book feels productive—but it’s an illusion of competence. It doesn’t improve long-term retention.

The Science: Research from Make It Stick shows that retrieval practice—actively recalling information—strengthens memory more than re-reading. The harder your brain works to recall something, the stronger the neural pathways become.

💡 Why this works: Forgetting is normal. But every time you struggle to recall something, it actually interrupts the forgetting process, making future recall easier.

🛠 Try this now: Instead of re-reading, challenge yourself to recall:

What were the main ideas you take away from the book you just finished?

What were the author’s key arguments?

If you had to summarize the book in 3 sentences, what would you say?

🔄 Example: Whenever I finish a book, I write a summary without looking at my notes. I ask myself: How would I explain this book to a friend? Which concepts do I actually remember? What’s one insight I want to apply?

I then publish my summaries on Goodreads or turn them into articles (for example here or here)—because teaching something is the ultimate test of understanding.

If you don’t want to publish publicly, try: writing a private book journal, starting a WhatsApp group for book summaries, or discussing books with friends. Just make sure you’re recalling from memory—not copying notes.

Step 3: Spaced Repetition — “Write Flashcards”

The Problem: Even if you understand something today, your brain will start deleting it tomorrow—unless you review it at strategic intervals.

The Science: Spaced repetition—reviewing information at increasing time intervals—has been one of the most replicated findings in cognitive science since the 1930s. It works because the harder it feels to recall something, the stronger your memory gets.

Researchers like Roediger & McDaniel found that spaced practice strengthens both learning and recall speed. Unlike cramming, which creates short-lived memories, spaced practice forms durable knowledge structures.

🛠 Try this now: To apply spaced repetition, you need a system to revisit key ideas over time. You can use a flashcard system like Anki (or Quizlet, Neuracache, RemNote, Brainscape, IDoRecall, Supermemo).

💡 Example: I use Anki flashcards for key insights from books. Instead of passively reviewing highlights, I create a question-and-answer format (more on that in a future Learn Letter).

Read Less, Remember More

Most people read for volume, not for retention. But learning isn’t about consuming more—it’s about remembering what matters.

Real learning happens when we engage deeply with the material, connect it to what we already know, and create systems to fight our natural forgetting curve. By elaborating on new concepts in your own words, retrieving information from memory rather than just re-reading, and using spaced repetition to strengthen those neural pathways, you transform passive reading into active learning.

Next time you pick up a book, slow down.

Ask yourself how it connects to your life, summarize it in your own words afterward, and revisit those key ideas through spaced repetition. Your future self will thank you when, months later, you can actually recall and use what you've learned instead of just vaguely remembering that you read something about it once.

Sources

Brown, P. C., Roediger, H. L., III, & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Make it stick: The science of successful learning. Belknap Press.

Bjork, R. A., Dunlosky, J., & Kornell, N. (2013). Self-regulated learning: Beliefs, techniques, and illusions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 417–444. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143823

Hass, D. (2015, February 11). This is how the brain filters out unimportant details. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/brain-babble/201502/is-how-the-brain-filters-out-unimportant-details

Radvansky, G. A. (2017). Human memory (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Reading this was like squashing that voice in my head that questions my intelligence. I didn’t know there was science behind my learning behavior, let alone a method to improve. I could have used this info decades ago before college. I do enjoy learning, so this will come in handy.

Thank you thank you! The universe came through again! I was just trying to think of a way to stop forgetting terms and things this morning. It’s frustrating to know it then not know it 5 minutes later. 🙃