The Science of Shower Epiphanies (And How to Have More of Them)

The neuroscience-backed system for engineering breakthroughs on demand.

Have you ever had the perfect solution strike you out of nowhere—while jogging, washing dishes, or in the shower?

It feels like a gift from the gods of inspiration.

But it’s not.

It’s a predictable, trainable skill.

In 2013, I was drowning in macroeconomics problem sets at my university in Frankfurt. For hours, I sat in the library, hitting a brick wall. My mind was a laser, but the target was nowhere in sight.

Frustrated, I gave up and went for a walk in the nearby Grüneburgpark. As my mind wandered with the sound of the rustling leaves, an idea began to form. A pattern from a lecture I'd forgotten surfaced, connecting to the problem I’d been wrestling with.

Click. The solution.

I used to think these “aha!” moments were accidents. I was wrong.

They are the result of a deliberate dance between two modes of thinking.

Understanding this dance doesn't just demystify creativity; it gives you a reliable system for producing it on demand. Here’s how.

Your Brain's Two Modes (The Pinball Machine)

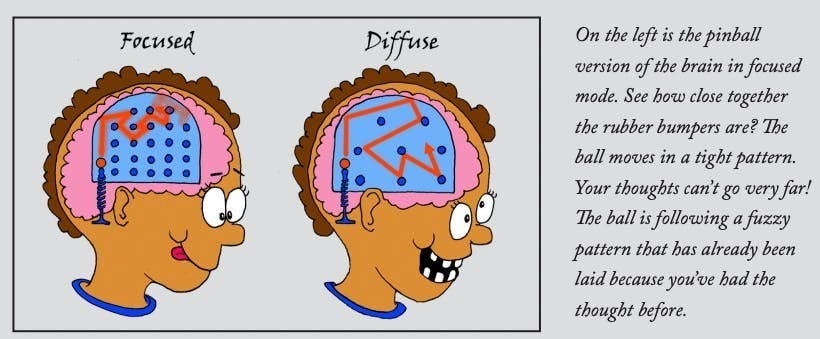

To understand this dance, think of your brain as a pinball machine and a new thought as the silver ball. Your ability to solve a problem depends entirely on how the bumpers are arranged.

Mode 1: The Focused Brain (Tightly Packed Bumpers)

The Focused Mode, is a pinball machine with bumpers packed tightly together. When you concentrate intently on a problem—analyzing a spreadsheet, writing code, or dissecting a report—you’re in focused mode. Your prefrontal cortex is in command, directing your attention along well-worn neural pathways. This mode is excellent for executing tasks you already know how to do and for the initial stages of absorbing new information.

The problem? The tightly packed bumpers keep your thoughts contained within a small area of the brain. You can find answers you already know, but you can’t easily make novel connections. This is why you get stuck. Your pinball of a thought is just hitting the same bumpers over and over.

Mode 2: The Diffuse Brain (Widely Spaced Bumpers)

The Diffuse Mode, on the other hand, is a pinball machine with the bumpers spread far apart. This mode becomes active when you stop focusing. Your brain’s “Default Mode Network” (DMN) takes over, allowing your thoughts to roam freely across the entire brain. The pinball can travel much further, making surprising connections between concepts you hadn't realized were related.

This is the neurological home of your shower epiphanies. You can’t be in both modes at once. The key to solving hard problems isn’t just more focus; it’s the strategic toggling between the two.

The 3-Step System for Breakthroughs on Demand

Here is a 3-step system, grounded in neuroscience, to move from hope to engineering of your breakthroughs.

Step 1: Load the Problem (The Focus Session)

Your diffuse mode can’t solve a problem it doesn’t know about. You have to give it the raw materials first.

The Science: Intense focus, even for short periods, loads the problem into your working memory and primes the relevant neural circuits. Neuroscientist Marcus Raichle’s work on the Default Mode Network shows it becomes most effective at problem-solving after a period of conscious effort. You must first frame the question before your brain's background processing can start searching for an answer.

🛠️ Try this now: Use a timer-based method, such as the Pomodoro Technique.

Choose one hard problem you need to solve.

Set a timer for 25–50 minutes.

Work on it with absolute, single-minded focus: no email, no phone, no distractions.

When the timer goes off, stop. Even if you feel you’re on the verge of a solution. The goal here isn’t to solve it, but to load it.

Step 2: Deliberately Disengage (Activate Diffuse Mode)

Your instinct when stuck is to push harder. Do the opposite. To find a new path, you have to get off the old one. This "incubation period" is creative rocket fuel.

The Science: When you switch off the focused mode, your brain’s default mode network—the diffuse mode—takes over. The science here is fascinating and more nuanced than simply “relax.” A landmark meta-analysis by Sio & Ormerod confirms that these “incubation periods” significantly boost creative problem-solving. The crucial factor is giving your brain a chance to restructure its initial approach after reaching an impasse.

While very low-load activities (like walking) are famously effective, some research shows that even moderately demanding but unrelated tasks can work, sometimes even better than pure rest. The key isn’t necessarily zero effort, but rather different effort. The goal is to engage your conscious mind just enough to prevent it from returning to the problem, which breaks your mental fixation and allows background processing to make novel connections. This is why the solution often seems to appear “out of nowhere” after a break; you’ve allowed the concepts loaded in Step 1 to be reassembled.

🛠️ Try this now: After your focused session, choose a "diffuse mode" activity. The best ones are often rhythmic or physical and don't require complex decision-making.

Go for a walk (without a podcast).

Take a shower or bath.

Listen to instrumental music.

Do a simple chore like washing dishes or folding laundry.

Doodle without a goal.

Step 3: Capture the Insight (The "Aha!" Moment)

An insight is a flash of lightning. If you don't capture it, it's gone. This fleeting thought is a new, fragile neural connection. You must solidify it immediately.

The Science: The "aha!" moment has a distinct neural signature. Research shows it's often accompanied by a sudden burst of gamma-band brainwave activity, representing a novel solution emerging from non-conscious processing into your conscious awareness. However, this moment of insight is not the end of the process.

To make it a stable, usable idea, you must immediately begin the process of encoding it into long-term memory. This is where you re-engage the focused mode. The act of writing, sketching, or verbalizing the idea does two things: 1) It forces you to elaborate on the idea, moving it beyond a vague feeling and giving it concrete structure. 2) It serves as a powerful form of retrieval practice. By pulling the nascent idea back into your conscious mind, you are strengthening its underlying neural connections, initiating its journey into long-term storage.

🛠️ Try this now: Always have a capture tool at the ready.

Keep a waterproof notepad in the shower (yes, they exist).

Use a voice memo app on your phone during walks or drives.

Have a simple notebook or app (like Google Keep or Drafts) for jotting down ideas immediately.

From Accident to Engine

Brilliant insights don't come from thinking harder. They come from thinking smarter, by following your brain's natural rhythm.

Stop treating epiphanies as random luck. Start seeing them as the output of a reliable, three-step process:

Focus Intensely to load the problem.

Disengage Deliberately to allow for connections.

Capture Immediately to solidify the insight.

Next time you feel stuck, don't push through. Step away. Your brain is designed to solve problems for you in the background. Trust the process.

Your challenge this week: Pick one nagging problem you're stuck on. Don't just work on it—run it through this 3-step process. Load it, walk away, and be ready to capture what you find. Hit reply and tell me what happens.

Resources

Brown, P. C., Roediger, H. L., III, & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Make it stick: The science of successful learning. Belknap Press.

Kounios, J., & Beeman, M. (2015). The Eureka Factor: Aha Moments, Creative Insight, and the Brain. Random House.

Oakley, B. (2014). A Mind for Numbers: How to Excel at Math and Science (Even If You Flunked Algebra). TarcherPerigee.

Raichle, M. E. (2015). The brain's default mode network. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 38, 433-447.

Sio, U. N., & Ormerod, T. C. (2009). Does incubation enhance problem-solving? A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135(1), 94–120.

Smith, S. M., & Beda, Z. (2024). The Past and Future of Research on So-Called Incubation Effects. In C. Salvi, J. Wiley, & S. M. Smith (Eds.), The Emergence of Insight (pp. 13–38). chapter, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Great explanation behind why we have that aha moment. Definitely something to consider the next time I come across something difficult.

This is brilliant. I do this often albeit intuitively. Thank you for breaking down the science behind it. It just makes so much more sense.